I always knew I wanted to attend a silence retreat at some point in my life. And over the years, many friends and even a few mentors recommended something called Vipassana. This is a specific meditation technique that emphasizes awareness of physical body sensations. It is frequently taught in the form of 10-day courses during which students remain silent the entire time. Students meditate for approximately 10 hours each day (with some breaks, fortunately), for a total of 100 hours.

Ten days of silence? 100 hours of meditation? Bah. Surely there must be a shorter option somewhere. But the alternatives I found were either very expensive or too vacation-like. So finally in March 2024 I made the time to attend a Vipassana course.

For the purposes of this blog I will not give a full day-by-day account of what I experienced (though if you are interested in that, feel free to contact me and I will gladly share)1. Instead I will focus here on key takeaways. However I should add a caveat: this is really something that must be experienced to be fully understood. It is something embodied, not intellectual. As the teacher explained: there is a difference between reading a restaurant menu and eating the food yourself. I think I discovered more about how my mind works during these 10 days than I did from reading any book. That said, here is some of what I learned:

It is the habit-pattern of the mind to wander.

No matter how much I tried to focus on my breath, my mind inevitably got distracted and drifted either to the past (memories) or the future (dreams, goals, imagined conversations, etc.). I learned how automatically the mind categorizes these events as pleasant (“that was nice, I want more of that in my life!”) or unpleasant (“that would be awful, I do not want that to happen!”). Dr. Fred Luskin at Stanford University estimates that we have, on average, 60,000 thoughts per day. That is a large number of pleasant or unpleasant events! With that much reinforcement, it is no surprise that these thoughts over time turn into cravings and aversions which in-turn have a huge impact on our decision-making. And it all seems to happen automatically, without any conscious effort or awareness.

What does this mean?

The mind wanders. Ok. That is somewhat obvious; no 10-day retreat needed. But the emphasis here is that this wandering (and the consequential formation of cravings and aversions) is habitual, i.e., learned and reinforced over time. With intention and diligence, it can be unlearned. Or at the very least, you can put it on pause for a short time and investigate how this habit-pattern is affecting you.

Doing that well requires understanding of another concept that becomes known (in a very visceral way) during the meditation journey:

It is the behaviour-pattern of the mind to react.

The mind constantly reacts to body sensations, based on the learned cravings and aversions. For example:

- Distant memories can be triggered by physical sensations.

- I was flooded with many memories of straining my neck over school books and tabletop games anytime I became aware of tension in my neck and shoulders.

- Thoughts of the future are also triggered by physical sensations.

- Moments of calm and tranquility evoked thoughts of future vacations I wish to take.

- When someone else upsets me, I am not really reacting to the situation; more accurately I am reacting to the unpleasant body sensations that the situation evokes.

- Even more accurately, I am reacting to the learned aversion to unpleasant body sensations.

- Fear may be evoked by a learned aversion to physiological reactions like a rapid increase in heart rate and burst of adrenaline (as I experienced when wandering the woods of the meditation centre during a break and hearing what sounded like a bear not too far away).

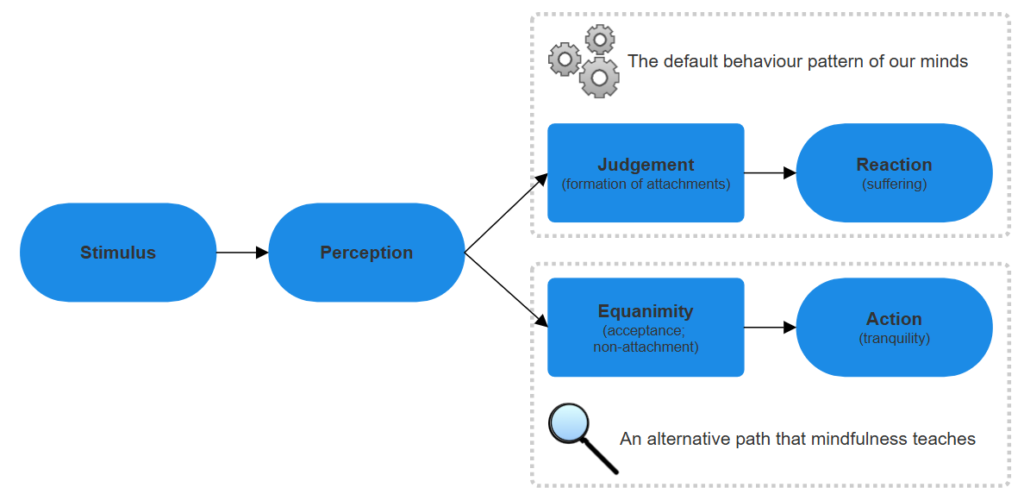

How can we stop (or at least limit) these automatic reactions? By slowing things down and practising equanimity: to observe and experience something fully, without reacting to it.

On the fourth day of the Vipassana course, students are introduced to what is aptly called “the hour of strong determination” (“adhitthana“). During this hour of meditation you conduct a slow head-to-toe body scan, all whilst you are not permitted to move. At first this was incredibly challenging. I never realized how frequently we subtly shift our posture without even noticing it. By the end of the first adhitthana hour I had tears in my eyes from all the pain in my legs.

But it became easier, surprisingly quickly. After a few sessions I was able to make it through the whole hour, and sometimes longer, without much trouble at all. In observing the pain you learn that the discomfort is produced entirely in the mind. The physical sensation itself is something very neutral, just like any other sensation. When you stop reacting to it, you stop suffering.. Oh.

You can learn new habits and behaviours.

What if we replace the Craving/Aversion → Reaction → Suffering cycle with some other approaches?

- Practice of awareness and equanimity: slow down the automatic processes and stay with observation. See what you find there. Noticing without judgment, categorization, labelling, and so on. Instead of “it is good” or “it is bad” just stick with “it is so.”

- Acceptance of change and impermanence: no physical sensation lingers for very long; it is constantly bubbling into something new.2 And our bodies are constantly changing, down to every cell. Electrical activity in the brain changes every moment. “I” have died a million deaths since yesterday. There is no need to cling to any self-concept, idea, or outcome. Change is a friend that need not be feared.

- Action instead of reaction: when we stop reacting, we are free to just act. To be intentional. To step forward with purpose and consciousness rather than being driven purely by the unconscious. To be content with action rather than preoccupied with outcome.

Equanimity is not indifference.

One of my barriers to embracing non-reaction and non-attachment was equating these ideas with dissociation and apathy. I asked the assistant teacher one day: it’s all well and good to try and not react to pain, but if I am supposed to stop my mind from craving things, should I no longer admire a sunset? Should I not enjoy the taste of good food? Should I not go home and tell my partner how beautiful she is? Should I not perform my work diligently if nothing really matters?

This was the teacher’s answer: equanimity is not indifference. There is no problem with noticing that you enjoy something. So long as you do not allow that enjoyment to turn into craving, longing, or obsession in the most extreme case. Similarly there is no problem with noticing that you dislike something. So long as you do not allow that dislike to turn into avoidance, frustration, or hatred.

To be indifferent (detached) is to dismiss our experience. Equanimity (non-attachment) is to notice and accept it.

Many of our “needs” are actually just strong desires.

I realized that many of the things I thought I needed—wealth, a dream home, popularity, creative success, bucket list experiences—are actually just desires shaped by lifelong conditioning towards some very rigid ideals. And if they are only desires, then it’s ok if they do not come to fruition.

This does not mean I am going to cease having any ambitions, or stop planning for the future. It only means I will not suffer as much in the event that things do not work out the way I plan or hope for. What a relief! Knowing this actually helps me step towards my dreams with confidence that things will work out one way or another.

I also learned that through the cyclic reinforcement of cravings and aversions, you can become addicted to craving itself. You can become addicted to challenge. And this addiction also can also drive reactions and consequential suffering. Nothing wrong with challenging yourself for the sake of growth, but I hope to continue to do so intentionally, rather than automatically to fuel a craving.

The truth is right under your nose.

Much of my professional and personal journey into neuroscience and psychology has served to chip away at that very existential question: Who am “I” underneath the layers of all my memories, experiences, and everything that has influenced me since birth? What is left when all of that is stripped away?

I think Vipassana meditation has given me at least a part of the answer: direct experience. Being fully present with one’s own body helps recognize a sort of “non-self.” Underneath all those layers is what I now call a source consisting only of a constantly shifting flow of sensations and experiences.3

Closing Thoughts

Overall it was an incredibly positive experience. I went into it expecting some laborious Herculean hero’s journey; a spiritual warfare, a battle with myself. What I found instead was simply a new way of understanding and working with myself. A collaboration rather than a fight. I left feeling much lighter; weight had been lifted that I did not even know was there in the first place.

Some Concerns

Sleep

I was initially dismayed by the schedule, which permitted only six hours of sleep per night. This ran against everything I emphasize in my clinical practice about how vital sleep is for health and mental well-being. But I soon realized why the hours for sleep are limited during the course: there isn’t enough time in the day otherwise! More time for sleep would lengthen the number of days needed to practice and integrate all of the teachings, and ten days is already a significant ask for our busy lifestyles.

I did find that by going to bed as soon as it was permitted and waking up just minutes before the first morning meditation session I was able to sleep about 6.5 hours on average, which was slightly more tolerable. Debriefing with my fellow students after the course I learned that some experienced difficulty sleeping due to all of the stuff that arose in their minds throughout the ten days. On the final day we were taught a gentle meditation style that focussed on compassion or “loving-kindness” for self and others. Someone made the good point that this may have been helpful to introduce midway through the course for those who were having a tough time, rather than at the very end.

Meals

You are provided with two buffet-style meals a day (breakfast and lunch) in addition to an opportunity for some fruit and tea in the evening. I’m a tall guy who struggles to keep weight on and worried this would not be sufficient for my body. I was relieved that this was not the case. I don’t think I have ever tried a vegetarian diet for ten days straight before, but it was incredibly delicious and filling! That was also useful to experience. I also developed a much stronger sense of how the food I eat (and how much of it) affects my mental processes.

Dogma

Every evening there was a one-hour pre-recorded video lecture by the late S.N. Goenka, a renowned meditation teacher who popularized this style of Vipassana. It was his voice that provided the meditation instructions (through audio recordings) throughout the course. The rationale seemed to be that he teaches it better than anyone else can. But I was vaguely concerned about there being a cult of personality around him, and a suppression of any opportunities for criticisms of the teaching. I suppose the counterargument would be that one attends a course to learn and practice, not to debate.

Some of the lectures were extremely insightful, certainly interesting, and overall I found them helpful. However, there were times when they delved into a particularly Buddhist worldview and very arbitrary metaphysics. Some of this was simply incompatible with my scientific training and I settled for accepting it as metaphor. There were many stories of the Buddha’s life, and for fairness I should also write that there were some Hindu and Christian teachings (stories, interpretations, allegories, etc.) mixed in. Much of the discourse was non-secular. There was no explicit attempt at conversion. But I sensed an implication that Vipassana was claimed as a universal solution for some very complicated questions. I also felt a little misled as there was much more Buddhism in the course than the school’s website suggested. Including a request (not a demand) on the first evening to take a vow to “surrender to Buddha” for the duration of the course.4 Not a problem for me, but I could think of people I knew who would likely have had a bigger issue with it.

My advice, if this is a concern, is to take what is helpful and disregard what is not. Remain skeptical of any universal claims that do not make sense to you. Focus on mindfulness meditation as a helpful tool (and not the only tool!) on your journey.

I would not quite call Vipassana a cult, but some of these elements certainly raised flags for me. I found these blog posts that address some of my concerns further:

- Is Goenka Vipassana a Cult? Short answer, yes. Long answer, no. [a brief, 5-minute read]

- Why Goenka’s Vipassana is so Culty [a longer, deeper dive]

I should note there are also many other Vipassana schools and teaching methods beyond the Goenka-style courses. I know little about those, so will not comment on them here.

How long-lasting are the effects of the Vipassana retreat?

Five months later, here is what I have noticed:

- I was able to maintain 30 minutes of daily meditation practice for almost two months after the course. Sometimes twice a day. This was not the two hours of daily practice that the teachers recommended, but it was much more than before. My practice lessened over the summer for extraneous reasons and I noticed the difference. I have resumed it now and again noticed the benefits.

- Ego returns. It desperately wants to. A 10-day course does not automatically cure all your faults. Rather, the course offers a deep understanding of the value of regular practice as a tool to manage unhealthy reactions.

- Regardless of how much or little I meditate, some takeaways from the course have remained (in addition to the more cognitive takeaways I mentioned above):

- It is incredibly easy to let go of things that used to bother me. Large things, small things, old things, recent things… The Vipassana experience completely changed my relationship with stress. I wish I had completed it a decade ago for that reason alone.

- A felt/somatic understanding of change as the one constant in life, and an almost effortless acceptance of it.

- The ability to rapidly tune into body sensations with very sharp awareness. It is like discovering a switch you did not know you had.

Would I recommend a Vipassana retreat?

For most people, yes, I think it can be very worthwhile. Especially if you’re curious about meditation or personal growth. However, those with severe physical or mental health concerns should consider it carefully. The application process involves a screening for this and conversations with the assistant teachers about any potential risks. Vipassana can be a powerful tool but it is no substitute for psychotherapy or prescribed medication, and the staff at the course are not trained to deal with crisis situations. I can only speak from my own experience, but I think you are setting yourself up for disappointment if your goal with Vipassana is anything to do with therapeutic progress or healing rather than something like curiosity and self-discovery.

For myself, it was an intense inner journey, and rewarding far beyond my expectations. Ten days of your life is a small price to pay for what could be gained. I am not sure right now that I would go do a 10-day course again but I am glad I did it at least once in my life. And there are many who return: one person there said it was his sixth time attending. I am somewhat curious about where a repeated experience would take me. Maybe someday. But for now, I plan to continue putting what I have learned into practice: equanimity, impermanence, and action.

I hope that my action of writing this reflection has been beneficial to you.

“May all beings find real peace, real harmony, real happiness.”

If you are interested to learn more about Vipassana as taught by S. N. Goenka, visit https://www.dhamma.org.

Have you thought about doing a Vipassana retreat, or maybe you’ve been through one yourself? Feel free to leave a comment below. I’d love to hear what you got out of it, or what’s on your mind if you’re curious about it.

- You can also find an excellent day-by-day overview of the process in the book The Equanimous Mind by Manish Chopra. ↩︎

- At some points later in the course, this constant bubbling of sensations coupled with strong equanimity all merged together into a very peculiar experience of a vibration or pulsing throughout my entire body. Perceptually there was not much else; no sense of solidity, no sense of a boundary between “me” and “not me.” I thought I was crazy, but learned this is a common experience among Vipassana meditators. It is sometimes called Bhanga which roughly translates to “dissolution.” It felt similar to frisson, but longer-lasting and not necessarily as pleasant. I am very curious about the neurophysiology of this experience. It seems there is very little research about it so far. ↩︎

- And here the ideas flow! I could explore all sorts of links between this source and Sartre’s concept of existence or Being, the idea of Ātman or “true self” in Vedantic philosophy, neuroscience pertaining to reduced Default Mode Network activity, the “being mode” described by Jon Kabat-Zinn, and even western apophatic theology. But that will all have to wait for another blog some other time. ↩︎

- It is only later explained that this means to embrace with an open mind the concept of knowledge or awakening as a guide during the course, i.e. the idea of Buddhahood, rather than surrendering to the historical Guatama Buddha figure in particular. ↩︎

0 Comments